Climatic and Biotic Controls on Topographic Asymmetry at the Global Scale

Neighboring terrain facing in different directions is not equally steep. This effect is caused by the complex interactions of geology, tectonics, vegetation, climate, and precipitation. Small differences in erosion processes lead to subtle variations in topographic form at the global scale.

We make the following main three conclusions:

- Steep terrain has more unequal slopes

- Pole-facing terrain is on average steeper than equator-facing terrain

- High-elevation and low-temperature regions tend to have terrain steepened towards the equator

This research has been published as: Smith, T., and Bookhagen, B. (2021). Climatic and Biotic Controls on Topographic Asymmetry at the Global Scale. Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface, 125, e2020JF005692. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JF005692

Global Topographic Asymmetry Magnitudes

We first divide the globe into a set of 0.25° boxes. Using those boxes as our analysis unit, we can calculate the average slope at each 1° aspect bin (e.g., the average slope facing in each unique direction). From this, we can calculate the center point of each slope-aspect distribution, which measures how north-south and east-west steepened a given area is. This leads to our first result – a global map of north-south topographic asymmetry.

There is a clear pattern of steepening reversal at the equator – terrain facing towards the poles is almost universally steeper. This pattern somewhat – but not completely – mirrors differences in received solar radiation: those slopes facing towards the equator will receive more sunlight over the course of the year. Hence, in general, slopes which receive less solar radiation are steeper.

The next question, then, is what is driving the development of this topographic asymmetry?

Measuring Asymmetries in Key Explanatory Variables

Many publications have discussed various environmental factors that can lead to topographic asymmetry. We explored several: vegetation density, temperature, freeze-thaw cycling, frost-cracking, aridity, evapotranspiration, potential evapotranspiration, and snow-covered area. While each variable goes some way to explaining the global topographic asymmetry trend, two stand out as the most important: vegetation density and freeze-thaw cycling (a general proxy for cold-weather processes).

Vegetation Density Asymmetry

Pole-facing hills can store more water—given equal vegetation cover, less water evaporates on the shaded side of the hill—which has a strong impact on vegetation density and composition. By using global high-resolution vegetation density estimates from Landsat, we can quantify the differences in vegetation density between terrain facing in different directions. Pole-facing slopes have almost universally higher vegetation cover, and the highest vegetation asymmetries are found in the mid-latitudes.

Freeze-Thaw Cycle Asymmetry

Using long-term MODIS data (2001-2020), we can count the number of days where daytime temperature rises above freezing, and nighttime temperature drops below freezing. We can then, for each of our 0.25° boxes, take the average north-, south-, east-, or west-facing freeze-thaw cycle frequency.

Cold areas have more freeze-thaw cycling on equator-facing slopes, while warmer areas will have more on pole-facing slopes. In essence, the asymmetric action of freeze-thaw processes is highly dependent on average winter temperatures – the highest asymmetries in freeze-thaw cycling are found in the mid-latitudes, where temperatures cycle above and below zero degrees more frequently. High elevations, for example in the Alps and on the Tibetan Plateau, also have large asymmetries in freeze-thaw cycling.

The Impact of Environmental Factors on Topographic Asymmetry

Insolation strongly influences land-surface temperature, which in turn impacts vegetation by controlling soil-water content, and cryospheric processes by driving both diurnal and seasonal temperature cycles, controlling frost cracking intensity, and modifying snow cover. It is clear from the global data that vegetation generally enhances poleward-steepening of terrain, and that low temperatures enhance equator-steepening.

The Role of Aridity

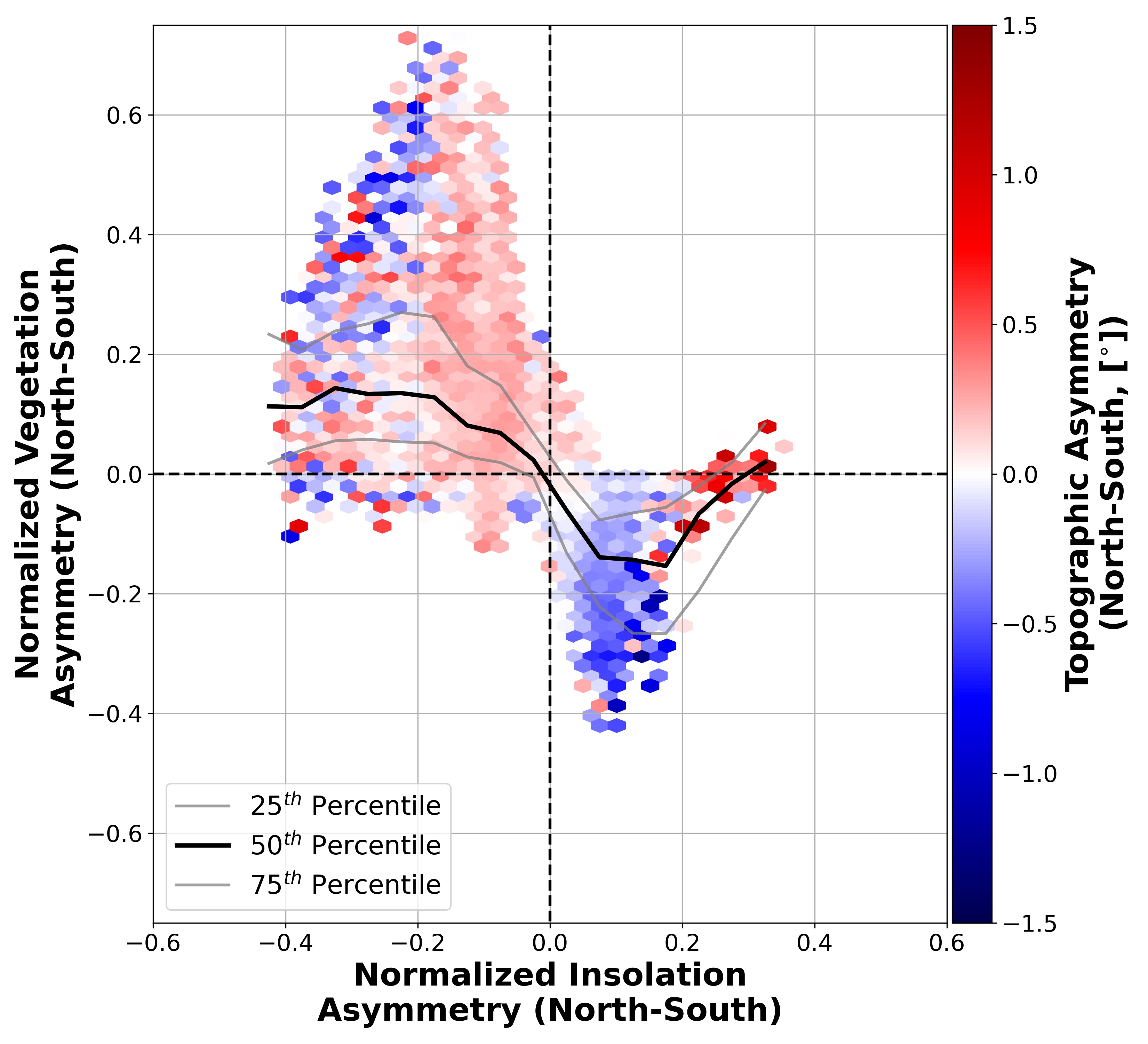

There is a striking insolation control on vegetation asymmetry: vegetation asymmetry is maximum around ±0.2, or a ~20% difference in insolation. At very low insolation asymmetries – for example, around the equator – and at very high insolation asymmetries – for example, at very high latitudes or steep slopes – vegetation asymmetries are fairly low. However, these end members represent two very different processes – low vegetation asymmetries in humid and tropical areas do not behave the same way as highly seasonal high-latitude vegetation. Medium insolation asymmetries associated with mid-latitudes generate the highest vegetation asymmetries, though not always the highest topographic asymmetries.

While most regions conform to the typical pattern of vegetation asymmetry encouraging topographic asymmetry, there are a few important outliers. Blue regions with high normalized vegetation asymmetry and red regions with low normalized vegetation asymmetry represent areas which are in opposition to the general trend of pole-facing slope steepening. In particular, the grouping of red points (topographic asymmetry values ~1-1.5) at negative vegetation asymmetry and positive insolation asymmetry (high latitude, southern hemisphere) indicates that vegetation cover is not the only factor controlling the direction and magnitude of topographic asymmetry in some regions.

The Impact of Steep Terrain

Terrain which is north-steepened or south-steepened can also be thought of as being poleward- or equator-steepened – essentially the sign of topographic asymmetry in the southern hemisphere can be reversed. By redefining terrain as either poleward- or equator-steepened, we can align the asymmetry estimates from the northern and southern hemispheres into a single metric, and use this to compare asymmetry over the entire globe to environmental and topographic metrics. We can also simplify this metric further by calculating its absolute magnitude.

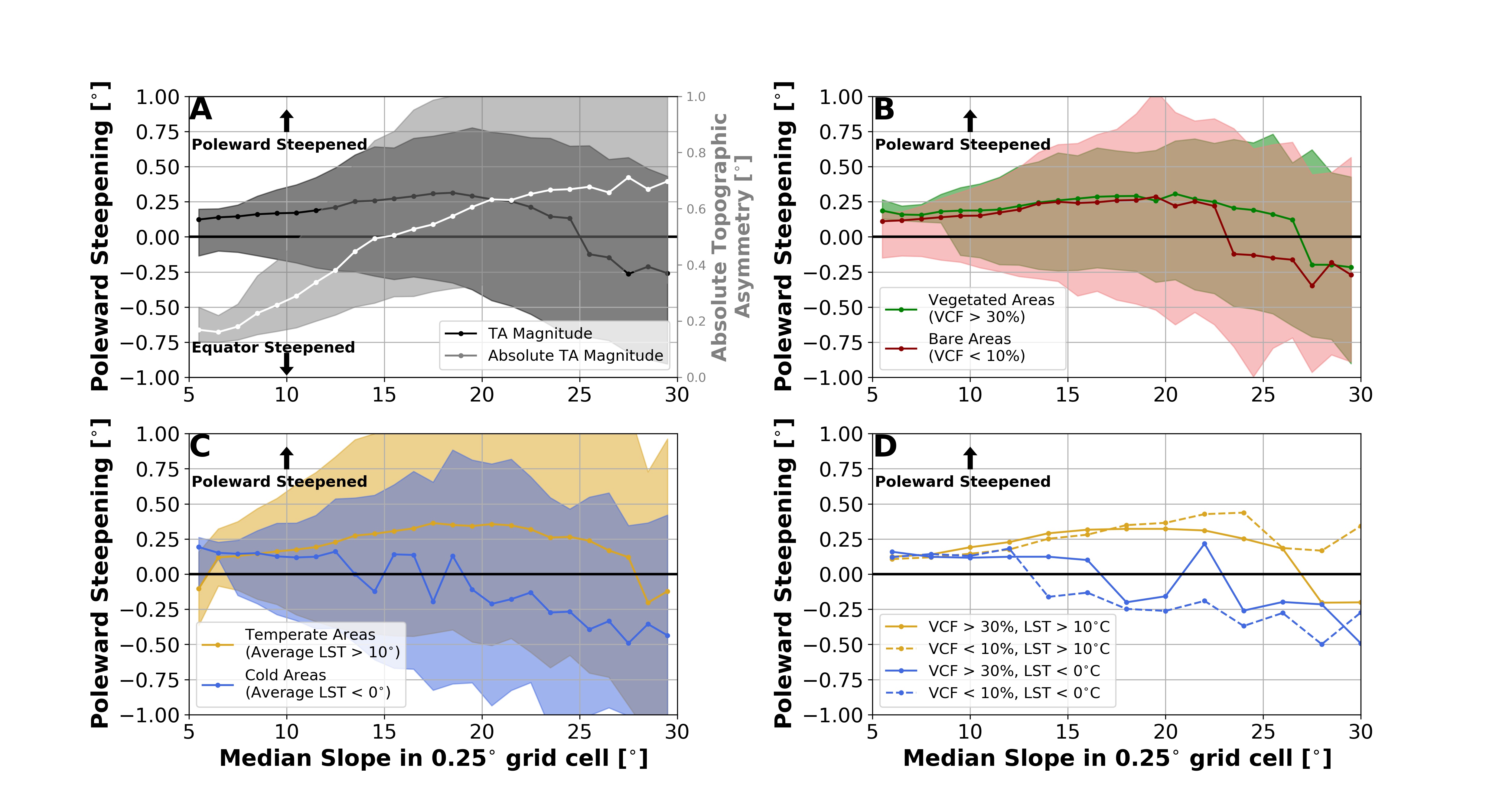

We find that the magnitude of topographic asymmetry is partially controlled by the steepness of the terrain; the absolute magnitude of topographic asymmetry – either pole- or equator-steepened – generally scales with terrain slope. When the relationship between terrain slope and topographic asymmetry is split between vegetated and non-vegetated areas, there is not a strong impact on the direction or magnitude of topographic asymmetry until 15° of slope. Above this threshold, vegetated terrain remains poleward-steepened as median slope increases, while bare terrain tends towards equator-steepening; this shift is, however, slight.

A similar relationship can be found when terrain is divided into temperate and low-temperature subsets – cold regions tend towards higher absolute topographic asymmetry magnitudes and more equator-steepened topography. To further disentangle the relative impacts of vegetation and temperature on topographic asymmetry, we have subdivided the data by both vegetation and temperature simultaneously. It is clear that while both temperature and vegetation cover play a role in controlling the direction and magnitude of topographic asymmetry, temperature is a stronger factor in driving the equator-steepening of terrain.

Implications and Takeaways

In vegetated landscapes, higher vegetation cover on pole-facing terrain encourages resistance to erosion by overland flow and diffusion. Hence, equator-facing slopes exhibit higher erosion rates where – all else being equal – diffusive and advective processes are more effective and generally result in shallower slopes. This is supported by the strong north-south vegetation density asymmetry observed at a global scale, and by the relatively stronger north-south topographic asymmetry signal observed in wet areas, where vegetation asymmetries are higher. Mid-latitude topographic asymmetry is relatively higher due to insolation controls on the magnitude of vegetation asymmetries; lower topographic asymmetry at high latitudes and around the equator partially reflects relatively low vegetation asymmetries.

In high elevation and cold environments, a different set of erosion processes play a role in the development of topographic asymmetry. Periglacial processes can encourage equator-steepening of topography via intense erosion on pole-facing slopes and headwall retreat. Pole-facing terrain in extremely cold environments remains frozen and stable for more of the year – indeed, in permafrost landscapes, the differences in temperature amplitude between pole- and equator-facing slopes can be quite large. Freeze-thaw cycling also acts more forcefully on equator-facing slopes, primarily through enhancing solifluction, slumping, and modifying soil-water penetration and overland flow. In high-relief and tectonically active environments, hillslope-transport processes will thus remove more material on equator-facing slopes. Where material transport is high, for example in steep river valleys, this material may not lead to gentler slopes at higher erosion rates. Even where material transport is low, slumping and mass movement could lead to terrain with steep upper sections and shallow lower sections rather than a more gradual and smooth hillslope form as is typical in mid-latitude regions.

The key points to remember are that:

- Steep terrain has more unequal slopes

- Terrain facing towards the poles supports more vegetation, and is generally steeper

- Low temperature regions often have steeper slopes facing the equator, where they receive more solar radiation

Leave a comment